Understanding Assistive Technology: How Does a Blind Person use the Internet?

Jul 2, 2019

Understanding digital accessibility challenges is easy if you know people with disabilities. But what if you’ve never seen a person who is blind use their computer or smartphone? We’re here to help you understand a little bit about what it’s like to use the internet if you have a disability.

What Do We Mean by “Blind”?

Blindness, like most disabilities, is a spectrum. There are people who can see nothing (not even light) and people who are legally blind and so many variations in between. When you meet a blind person, even one who uses a guide dog or a white cane, it is unlikely that you will be able to tell where they fall on this spectrum. (And they may have completely different vision in one eye than the other.)

Today, we’ll be focusing on those who require a screen reader or braille keyboard to access technology.

Assistive Technology Used by Blind People

Assistive technology (AT) is a broad term that refers to hardware and software that enable people with disabilities to access technology. For those who are blind, the main AT are screen readers, braille displays, and speech recognition software.

Screen readers

Screen readers have been around for more than 30 years. A screen reader is a program that analyzes the layout and content of a website and provides a text to speech translation. The playback speed can be set by the user and commands allow them to skip from heading to heading, click links, and do other important tasks. Much like how a sighted person can visually skim a website to find the section they want to read, a person who is blind can do the same with their screen reader—as long as the website’s content has been coded with proper header tags.

Built-in examples of screen readers

- Apple’s iOS VoiceOver

- Android TalkBack

- Kindle Text-To-Speech

Software examples of screen readers

- Microsoft Narrator

- JAWS

- NVDA

- Fusion

Refreshable braille displays

A braille display is a flat keyboard-like device that translates text into braille and enables blind or deaf-blind individuals to read text using their fingers.

A braille display is a flat keyboard-like device that translates text into braille and enables blind or deaf-blind individuals to read text using their fingers.

Examples of braille displays

- Focus (Freedom Scientific)

- Brailliant (Humanware)

Software that supports braille

- iBrailler Notes

- Google Braille Back

Dictation

Speech recognition software allows a user to navigate, type, and interact with websites using their voice.

Built-in examples of dictation software

- Siri

- Apple Dictation

- Windows Speech Recognition

- Google Docs Voice typing

Software example for dictation

- Dragon NaturallySpeaking

Accessible Design for Blind Users

Here are some accessibility issues that restrict access to people who are blind:

Keyboard accessibility

Not providing access through the keyboard on websites is a major roadblock for blind and keyboard-only users. Can you use your website or program without a mouse? Use the tab key, arrows, and enter to navigate.

Pop-ups

If sites fail to set reading focus appropriately, a pop-up dialog can prevent a blind user from moving forward”¦ or even knowing how to get back to where they were.

Cluttered pages and carousels

Cluttered pages with carousels and moving text aren’t user friendly for blind users. (Spoiler alert: They aren’t user friendly for many people.)

ARIA mishaps

If sites misuse ARIA markup, it changes a screen reader’s behavior in a way that interferes with navigation and operability.

Document heading and labeling

Without proper heading tags, a screen reader user cannot quickly locate what they want to read.

Clear links

Linked text should be able to stand on its own. For example, “Read our latest whitepaper on digital accessibility” stands 100% on its own and makes sense. You know what you’re getting. If you just linked “latest whitepaper,” that doesn’t make sense on its own.

Alternative text

Images that convey meaning need to be tagged with alt text so the person who is reading your website can hear a description of the image.

The Good Life: What an Accessible Site Looks Like

Level Access’s principal accessibility architect, Sam Joehl, who is blind, explains it best:

- A good site uses proper semantic markup to allow individuals to non-visually understand the page structure and hierarchy. This also enables individuals to navigate to section headings and document landmarks on the page.

- Link text clearly identifies the purpose or destination of the link and does not use ambiguous phrases such as “click here” or “read more.”

- Images that convey meaning are tagged with alternative text that gives an accurate description of the image.

- Instructions are presented in a manner that does not require vision (such as, “Click the red button at the top right corner of the screen”).

- All controls are clearly labeled, easily identifiable, and can be operated from the keyboard.

- Pages are not overloaded with content and they make performing the desired task easy.

- Unnecessary information is not initially displayed and a progressive disclosure approach is used so the user can expose additional information through activation of a control such as a “show more” button.

- When new content appears on the page, an announcement is made to alert the user and the new content is easy to locate or focus is set to it.

Using Mobile Devices

Smartphones have opened up new possibilities to blind users. Now, people who are blind have apps that help them recognize money, identify colors, scan bar codes and read product information, and help them navigate in new cities.

How does a blind person use a touchscreen?

We’ll answer that question with another one:

Think of your favorite app, one you use every day. Can you visualize the user interface for that app?

Do you know, for example, where the “Pay” button is on your Starbucks app, the “Play” button on Audible, and what to do when the phone rings?

When accessibility features are turned on, a layer of audio feedback is added to each tap on the screen. A blind person can tap on the screen in a particular area and hear information about what they have tapped. They can tap again to activate that area (i.e., open that app or click on a button or field within the app). Thus, even those with no vision can understand what is on the screen based on audio feedback.

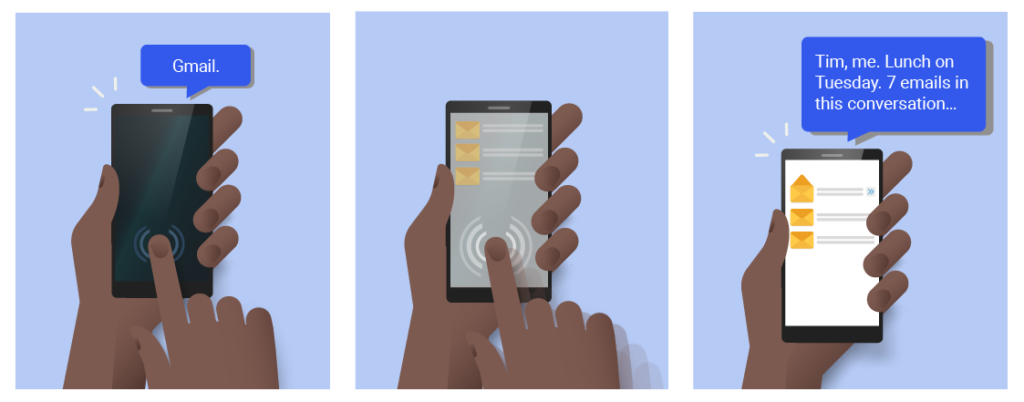

The image below shows someone opening the Gmail app on an iPhone using VoiceOver. A single tap announces that the person has tapped the Gmail icon. A double-tap opens the app. VoiceOver then reads the details for the top message in the inbox.

Why is iPhone popular with people who are blind?

Apple has the most mature accessible smartphone on the market, allowing for reliable features to work for most blind users. Apple bakes accessibility into its native controls and framework. Thus, apps that are written for iOS are more likely to be accessible, without even meaning to be.

Labeling location and purpose

For iOS VoiceOver and Android’s TalkBack to work properly, clear labels are key. Labels should represent the location and purpose of the element that has focus.

Don’t forget gestures

Gestures such as tapping, swiping, and pinching are vital for users who are blind. When apps do not respond to native or modified accessibility gestures, it makes it difficult or even impossible for some people to use.

The Bottom Line: Design to Include Blind People

You can design your websites, software, and hardware with these blind people in mind and you can retrofit existing technology to be accessible. It’s a win-win situation for your organization (more clients, more revenue, more contracts) and people with disabilities (less confusion, less frustration, less isolation). Some fixes, like auditing your content structure and alternative text, are quick to do and make a big impact on the user experience.

Special thanks to Sam Joehl, Meaghan Roper, and Jaclyn Petrow for their contributions to this blog series.

Subscribe for updates